Unlike the game of draughts (checkers) played almost everywhere else in the world, the game in Québec is played on a 12 x 12 board with 30 pieces per player.

The game is played otherwise by the same rules as International Draughts.

The Association québécoise des joueurs de dames (Québec Draughts Players Association) has put on line the Traité Canadien du Jeu de Dames à la Polonaise from 1906, as well as the Manuel du jeu de dames canadien from 1922 (both in French) – both interesting from a historical point of view.

It seems that the game is popular in Québec and played there alongside 10 x 10 International Draughts. Only on the other side of the world is draughts also played on a 12 x 12 board. Wikipedia states that in Malaysia and Singapore the game is played on a 12 x 12 board without backwards capture, but provides no verification for this. In Sri Lanka the game is also played on a 12 x 12 board – here it is called Dam, hinting at a Dutch origin. The AQJD itself says that “Canadian checkers (144 squares) [is] played mostly by francophones from North-America (but also in Sri Lanka and Dominican Republic)“.

Where did the variant come from, and is its appearance on two opposite sides of the world merely coincidence?

The AQJD have their own version of their game’s origin:

“Legend says that the Canadian game of checkers was introduced here by a voyager who, after having discovered the game in Europe, tried to reproduce it, adding a row of squares all around.”

However, draughts on a 144-square board was not unknown in nineteenth century Europe either. A part of the introduction of the Traité du Jeu de Dames by Van Damme, published in Gent, Belgium, in 1871, says: “We again introduced the game of checkers on a 144 squares board, named the double checkers board. Each partner having 30 pieces. This game is unquestionably more complicated than the modern game and offers wider combinations, but the 100 squares game already offers so many resources that we’ll never be able to know all of its artifices.”

Murray says that boards for 144-square draughts were on sale in London in 1805, though this is difficult to verify.

Sri Lanka/Ceylon

Sri Lanka was heavily influenced by the Dutch East India Company between 1640 and 1796 when it fell to the British. Malacca in Malaya was also ruled by the Dutch between 1641 and 1975.

In Ancient Ceylon, by H. Parker (1909) the game is described. Parker says that it is played also in India. His rules for the game – Dam, which he translates as ‘the net’ – differ from those of Canadian draughts. In Sri Lanka Parker says that the pieces (30, as in Canadian draughts) are placed on the white squares and may move backwards as well as forwards from the start of the game, but only to the next adjacent square if they have not been crowned. A piece, once crowned, may move as far as it wishes along a diagonal as long as its path is unoccupied by its own or opposing pieces. It may make long captures, but only if each opposing piece has a vacant square after it. A king can continue its move, if it reaches the end of a diagonal, by ‘bouncing’ along the corresponding diagonal at right angles to the first, on condition that it captures one or more opposing pieces on each diagonal. It may continue its move as long as it does so. If the king captures no pieces on the first or subsequent diagonal, it ends its move at the end of that diagonal.

Malaya/Malaysia

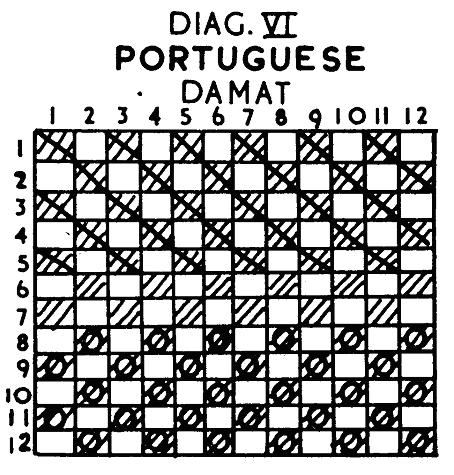

W.H. Newell, writing in MAN (February 1959) says that the Portuguese at Malacca played draughts on a 12 x 12 board, calling it Damat. His accompanying diagram shows the long diagonal at the players’ right-hand side, though this may be an error:

He also provides a slightly confused description of the move of a crowned piece:

“When a piece gets to the opposite end of the board it becomes a king and can travel any distance along the black squares in one move in one line provided that there is a vacant space at the end of its jump.”

He states that this is a local rule, but as the same rule exists in International Draughts he may have been mistaken, being probably more familiar with English draughts where the King captures in the same way as an ordinary piece (” … from one square over a diagonally adjacent and forward square occupied by an opponent’s piece (man or king) and on to a vacant square immediately beyond it.”), but is allowed to do so either forwards or backwards.

Arie van der Stoep, in A History of Draughts (1984) notes that 12 x 12 boards were not unknown in India even before the arrival of the Europeans, where they were used for chess variants. It is not impossible that the game of draughts was transposed to an existing board size. The likelihood of the game evolving independently from Alquerque, brought by Arab traders, and having by and large the same rules as International Draughts, is implausible.

If the imported European game of draughts was transposed to a 12 x 12 board in Sri Lanka, southern India and Malacca, with almost exactly the same rules as the game in Québec, this would be a very unusual case of parallel development. As such, it is also quite implausible, and the conclusion must be drawn that a game on a 12 x 12 boards was indeed known and played in Europe in the 18th century, and that it was carried by colonists both east to south asia and west to Québec, before dying out in Europe.